Lookout Elevation: 9,495 feet

County: Jackson

In 1910, an ascent from Four Mile Lake of McLoughlin was done by Forest Assistant Harold D. Foster and his crew of cruisers. They reported a good view except toward the Rogue River Valley, where it is smoky. No forest fires in Applegate or Ashland part of the forest were seen. (It seems they were just climbing up for the day and no lookout person was stationed there).

By 1916, Mount McLoughlin was being considered as a lookout. As the highest mountain in the region, everything is visible in clear weather. The success of the Mount Hood station suggested the possibility of the use off Mount McLoughlin as a lookout. Harold D. Foster had some serious considerations however. These are his words. He said the snow lies so deep on the mountain that it would be probably not safe to attempt the ascent, even without a load, before the first of July. Also, the prior year in 1915, it was noticed there were several days in late September, before the first fall rain, when fog hung over the top of the mountain all day and through this fog an observer could not have seen. During the most critical period of the fire season, when if ever a lookout would be needed, the mountain was useless. During these days all the other lower peaks in the neighborhood were free of fog. The ascent is very steep, the last thousand feet being almost precipitous, along a narrow ridge and many great blocks of lava. All equipment and all fuel would have to be packed on mens backs. I do not think a man could live on the summit unsheltered except during the warmer hours of sunlight during milder days. The cold is so intense and the wind so strong as to be unendurable. This is my opinion, based on observation of the peak in all weathers. The protection of a closed house would be essential even in mid summer. Nothing but a steel or stone house could stand, and the cost of construction when everything must be packed up the mountain on mens backs would be excessive. Once established and housed, the observer would require the almost constant attendance of an assistant to pack fuel and supplies up the mountain. He himself could not attend to this, for it would take him practically all his time. The mountain is the lava cone or plug of a volcano that has been eroded away. This lava is a reddish color from the presence of iron. It is often been noticed that lightning is attracted to the mountain. In case of a lightning storm the observer would be in imminent danger of his life and since the entire mountain is mineralized could hardly get to a safe place. It is not believed that Mount McLoughlin can supersede other lookouts, or even any other one. It would be but an additional station; and in view of the difficulties and expense of a lookout on this peak, it does not seem a practicable proposition.

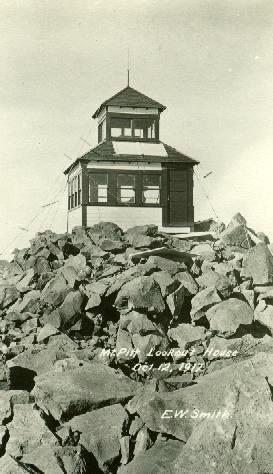

In 1917, the forest service received a rushed order of three lookout houses and one was for Mt. McLoughlin. It had been decided to construct a trail suitable for burro travel to the very top of the peak, and the lumber was to be then be packed on the backs of these animals. A phone line would also be constructed and the site would replace Robinson Butte. It was estimated that the observer on Mt. McLoughlin could see fires for a radius of 75 miles from the top. On June 30, Forester George H. Cecil, of Portland, placed an order with the Mill-Made Construction company, of Portland, for the cupola style lookout. Ten mules were expected to be used for transport. All the material for the building was trucked from Medford to Klamath Falls, and then packed over a 12-mile trail by Dee Wright, government packer. No piece of timber for the entire building was over eight feet in length. The first lookout was Ernest W. Smith in September who planned to bring his wife up once the lookout structure was completed. It was finished at the start of October. He was able to make light flash signals up to 20 miles away.

In 1922, the lookout was J.F.G. Cone. He would be the lookout for the next 8 years. He was described as a sociable hermit of Mount McLaughlin. During his 5th year, he was described as the following by the Sunday Oregonian newspaper: In 1922, a man with a full beard, and long black hair, clad in loose fitting blouse and a lower garment resembling track pants, came to Rogue River Valley. His tattoo marks proclaim that he had once been a sailor and he said he had served in the French navy. He has never left Jackson County since that time, yet no one knows more about him. Cone has lived in the summer among lightning bolts on top of stormy Mount McLaughlin, a government forest fire lookout. In the winters, he acted as watchman for summer cabins at Lake on the Woods. He has now bought a tract of land in Pheonix, near Medford, and plans to move all his earthly goods--consisting of innumerable books, even less clothing than the modern stenographer wears and a set of laboratory test tubes. Cone, who on occasion has claimed, to be a Basque or an Arab, is not averse to an audience. Much of his time has been spent reading and he delights to talk of science, or of his theories of the ideal way to live. He is a vegetarian and refuses to kill even mosquitoes. Tennis shoes and two pieces of clothing are his regular year-around garb. His body is lean and tanned. His age he professes not to know, but he appears to be no more than, 35. Unlike the general run of hermits, Cone has no autographed pictures to sell and he avoids the camera.

J.F.G. Cone, pronounced KO-NAY was described by the Klamath Herald in his 8th year as follows: He is one of the keenest eyed men in the service, being the first to spot a disastrous fire in the Fandango unit of the Modoc National Forest, miles away, over in California. Although of unusual intelligence, Cone is freakish in his dress, assuming a garb that makes him look something an Assyrian. Wearing bright yellow clothing of thin lined material in all kinds of weather, his wardrobe includes a Tam-O-Shanter cap, shirt, and trousers that stop well above his bare knees. He has no other covering except socks and tennis shoes. Thus attired, Cone looks like a Shell Oil station ducking through crowds he attracts more attention than all other shoppers put together. But after you stop him for conversation, you will discover one of the most pleasant-spoken, well-informed men you have been privileged to meet. Cone says that electrical storms are frequent up where he sojourns from May to September and occasionally the terrific bolts burn out his telephone and demolish the wire for a distance of a mile or more. During some of the disturbances, the lookout says, he has sat in his cabin and watched rocks blown to smithereens as some ambitious charge tried its hand at rock crushing, and the resultant crack of thunder is deafening, he adds. In the hot month of August when people in the lowlands are sitting on cakes of ice and fanning themselves with dustpans in order to keep cool, Cone says he will enjoy a fine blizzard at his summer home on Mt. Pitt. Terrific winds and blinding snows with the thermometer at freezing duplicates the January holocausts in North Dakota, at a time when summer in the valleys is at its heights, concluded the lookout, who early in September takes down his shingle and moves back into town again for winter." (Klamath Herald)

In 1925, a letter to J.A. Howarth, Klamath Agency, from Hugh Rankin, Crater National Forest: Mount McLoughlin, although used for the past several years, is not satisfactory as a lookout point. A few weeks ago I was on this mountain and found that I was unable to see the east side of Klamath Lake sufficiently clear to determine a fire or its location. I judge from this experience that quite frequently, and especially in the forenoon when the sun is in the east, it is very difficult to locate a fire on your district from the top of this mountain. I believe that the unsatisfactory service is caused by the height of the peak rather than any fault of the man himself. In looking down on the country the impression is of looking into a dark well. For the coming season our recommendation will be for the use either Devils Peak or Mount Pelican, either of which I believe will render you better service.

In 1926, an electrical storm put all telephone wires out of commission at Crater National Forest Headquarters, so they closed the lookout station on the summit of Mt. McLaughlin for the last part of the season.

In 1928, the lookout Cone telephoned that a 61-mile gale which blew across the mountain the night before lowered the temperature to 32 degrees at 7:30 p.m., and to 31 degrees at seven in the morning. August 2.

In 1930, J.F. Cone, after eight years, refused to take that position because of the dangerous condition of the lookout building, and instead took a lookout position with the Cleveland National Forest in extreme southern California, next to the Mexican border.

In mid-summer, Assistant Supervisor N.C. White and Ranger E.J. Rogers spent a day at Mt. McLaughlin selecting a location for a new lookout station. The lookout building was an unsafe condition because the base beneath was steadily slipping away. The lookout building was not used this year, instead the lookout stationed there, E.E. Cottman, was in a tent nearby. Mr. Cottman had come into the city the day before and resigned his position both because of an injury to one of his eyes and the serious illness of his mother in Washington state. Ernest Smith finished the fire season as lookout. It had been quite cold and windy high up on McLaughlin's summit. The lookout building for some time past had been anchored to a huge rock to keep it from slipping down the mountain. Continuous action of the elements had undermined the cliff on the northeast side of the peak on which the house rested. Work of preparing a solid concrete base for a new lookout building was started. The new house would rest on a cement and stone foundation three feet through at the base and 14 feet in height. Long steel rods buried in the foundation serve as braces and steel cables keep the house rigid against storms. The new structure was slightly larger and was ordered.

In 1931, a new lookout house was completed. Twenty-three windows circle the building and the latest lightning protectors were installed.

In 1933, the lookout was James Radcliffe of Medford, he took up duties about July 1.

His mail and supplies were to be delivered twice a month by a packer. On July 21, Lester Moe and Robert Snyder showed up to take panoramic photos from the roof of the cab.

In 1935, the lookout was unoccupied for the first fire season. No reason for the change was given by Hugh Ritter, the District Ranger. It would not be used again.

In 1936, the lookout was officially abandoned in favor of lower points such as Robinson Butte.

In 1952, papers reported the building is in such a state of disrepair that it is feared it will fall on someone who might seek shelter there. The lookout was reported as abandoned because of its being such a distance from the timber that the fire finder was not effective.

In 1955, the lookout was destroyed. Vandalism and misuse of the lookout was the reason for the destruction of the building, according to Robert French, a member of the crew sent to the summit to push the structure over the side of the peak.

Mount McLoughlin Lookout

WillhiteWeb.com

For original articles, see Ron Kemnows Page:

Story years later after Cone was staffing (possibly embellished)

"At one time, Cone conceived an idea for preventing forest fires caused by lightning during a thunderstorm. He constructed a large system of antennas and wires with hopes of drawing off all the electrical charge in the air within a large radius of Mt. McLaughlin. The first time this plan was tested, it back-fired. All of Cone's equipment was destroyed by a nearly - direct lightning strike. A frightened and speechless Cone appeared at the Lake of the Woods ranger station following the storm and refused to return to his station. Ansil Pearce finished the season as lookout." (Herald and News on May 11, 1958)

(Poem by Ernest Smith while building the lookout house)

1917: "Here I've been now six weeks working,

helping build a lookout house

For the forest service lookout, to help

save the fearful loss

From the fires that burn the timber. Tho

I'm sometimes lonely here

Still I love this grand old mountain and

will always hold it dear.

They may call it Mt. McLaughlin, but twill

always be Mt. Pitt

To the people who live near and look with

pride and awe at it."

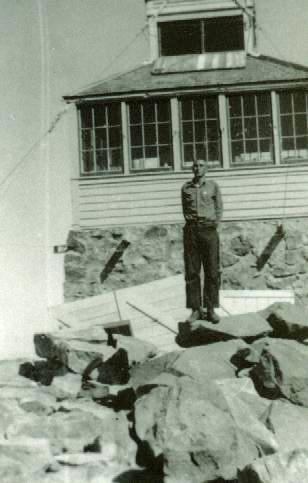

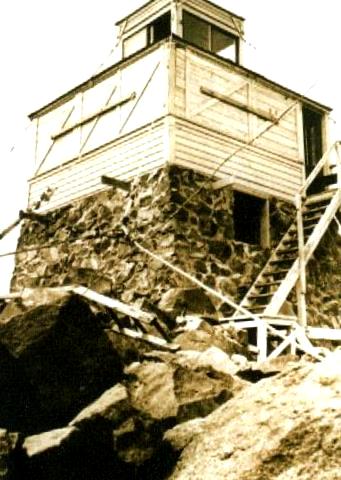

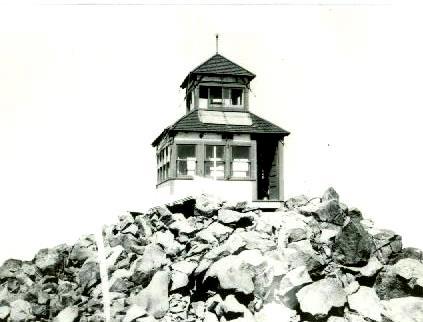

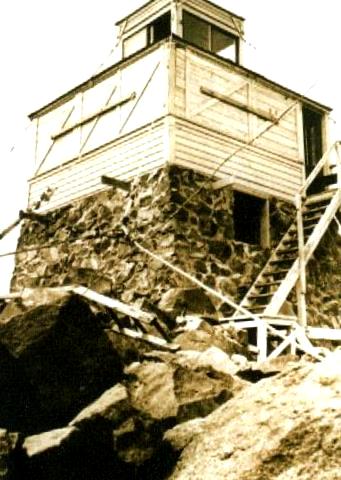

1934, second lookout

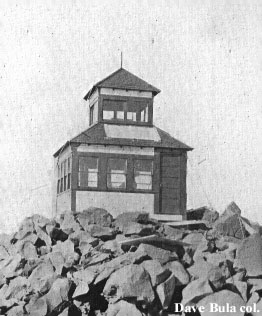

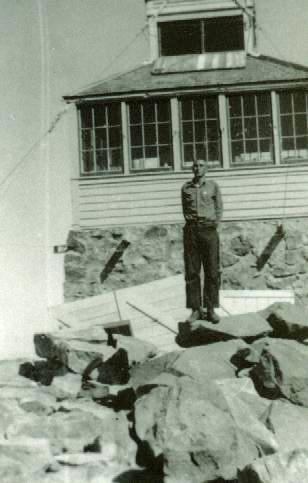

1920

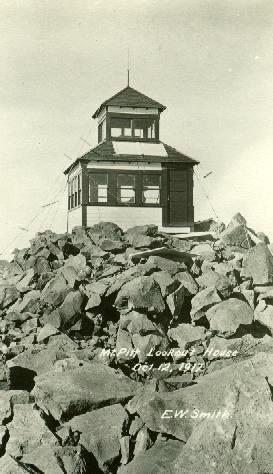

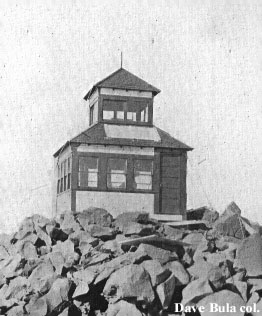

1917 origional lookout

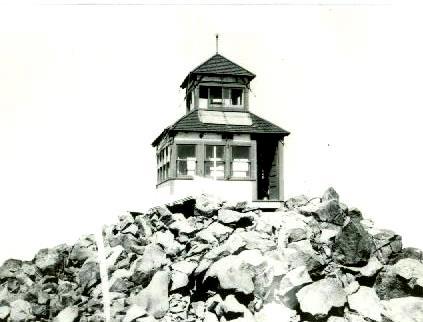

No date but same as image abvoe

No date, second lookout, Mark Swift collection

1917 original lookout under construction

Locals call the mountain, Mt. Pitt

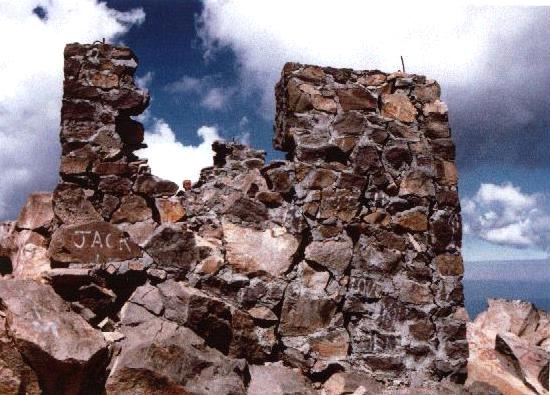

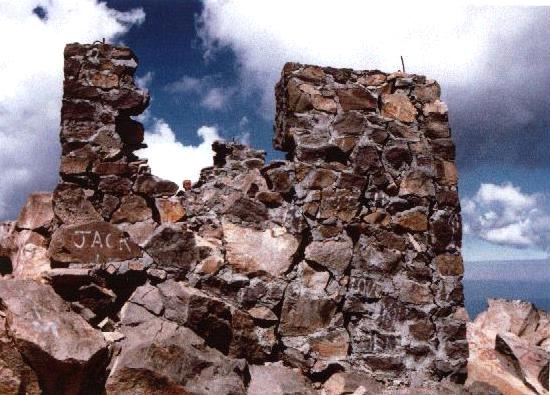

1987 foundation of second lookout

1973 foundation of second lookout (photo by Tom Lopez)