Mount Hood Fire Lookout History

WillhiteWeb.com

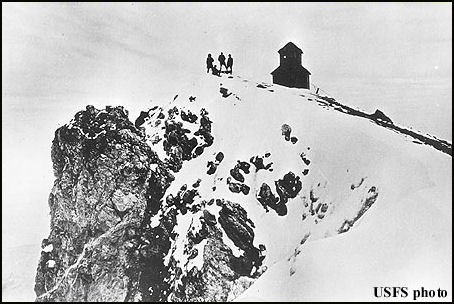

This lookout was the highest in Oregon, and has a fascinating history as shared below. Many thanks go to lookout enthusiast Ron Kemnow for finding all the news articles to piece the story together about the Mt. Hood lookout. I have seen dozens more photos of the lookout. Once I see them again, I will save them and add them to this page.

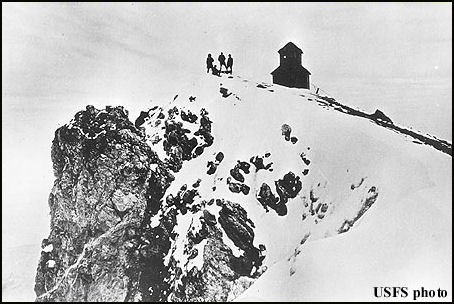

Elevation 11,239 feet

Hiking Distance: 3 miles (South Side/Hogsback Route)

Elevation Gain: 5,300 feet

Access: Paved

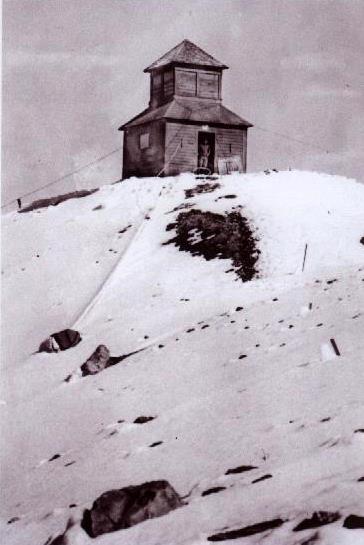

Year 1915

Year 1916

In 1915, the USFS placed a firefinder on top of the summit and a tent with a wooden floor. This temporary camp would be used this first summer until a cabin could be built. The lookout man was fire warden Elijah Coleman. Mr. Coleman had been a guide for 18 years and by the end of his season on Mt. Hood in 1915, he had climbed the mountain 357 times.

Establishing A Phone Line

Elijah Coleman, ranger George Ladford, and lineman Roy Garwood brought up telephone equipment in mid-July and established a direct line of communication to Portland. One of the first calls was to the Oregon Daily Journal editorial room to share the news. The newspapers responded with many articles about the achievement of having a fire lookout camp on the summit and the potential to protect the entire region from fire outbreaks. Just sleeping on the summit for weeks at a time was considered an incredible achievement given the elevation and storms. This made Elijah Coleman a local celebrity working at his station.

The latter half of September was spent carrying 10 tons of lumber and materials up the mountain for the first permanent structure, a cupola cabin. Twenty mules carried the lumber by pack train from Government Camp up to Crater Rock, just a quarter mile from the summit. The final segment was done by 10 husky men who carried the lumber up to the summit. Upper mountain work was under direction of Elijah Coalman, and George Ledford. The packing to Crater Rock was directed by Dee Wright and John Williams.

By September 28th, all the materials were on top of the mountain and construction begin immediately according to T.H. Sherrard, Assistant District Forester. No mishaps were reported by any of the men during the difficult climbing between Crater Rock and the summit. This is impressive considering that a few weeks later in October Elijah Coalman slipped as he was coming down the mountain and fell down a crevasse, a distance of 30 feet. A shelf of snow on the side of the crevasse was all that saved him from going the rest of the way. Mr. Coalman escaped with a swollen ankle and a thrilling story.

In September, a wedding was performed on the summit between a Miss Blanche Pechette of Wapinita, and Frank Pierce of Rowe. The ceremony was held in the tent of the lookout Elijah Coalman. The marriage was performed by Rev. G.E. Wood of Rowe. A wedding breakfast was served in Coalman's tent. In the evening the summit of the mountain was illuminated.

Getting Lumber Up the Mountain

First Wedding

In early September, Mrs. E.W. Senior of Salt Lake City and her daughter, Miss Ruth Senior, were obliged to remain at the top of the mountain all night because of a severe storm which sprang up while they were making a perilous ascent and which so numbed and chilled them that there was danger of freezing to death if they left the shelter of the lookouts tent at the summit. The guide cut steps in the ice and the rest held to the ropes, which they found very difficult, because their hands were so numb and cold. However, at 3:30 in the afternoon they reached the top, where a lookout tent is stationed. The lookout Elijah Coalman, was apparently quite a hospitable host and soon made the party very comfortable. These two women, along with Mrs. L.F. Pridemore of Oregon, held the distinction of being the only women who had ever passed a night on the summit of Mount Hood at that point in time.

Unexpected Guests

One of the first fires Elijah spotted was in early August when he sighted a smoke, contacted the Stanley-Smith Lumber Company, who quickly dispatched a fire crew to the scene. Presumed to be started by blackberry pickers, the fire burned about 300 feet of a logging flume and within an hour would have been a major fire. During the first year, Shirley Buck, the acting assistant district forester said the lookout had had far surpassed their expectations, allowing the lookout to detect fires from 50 to 75 miles distant. Other fires spotted and reported to the ranger stations were the White River and Shell Rock creek fires (both started by lightning), and the Salmon River fire (cause not determined).

Spotting Fires the First Summer

There was a practice of lighting up the summit of the mountain. It was mentioned earlier in the wedding in September. Another article on October 9 said that another illumination would take place that night. According to the plans of Lou Pridemore, the proprietor of Government Camp Hotel, and with the help of Elijah Coalman, the peak was to be illuminated at about 8 p.m. Two hundred pounds of red fire had been taken to the top of the mountain. Cloudy condition of the atmosphere were a concern that would prevent city watchers from seeing the blaze.

Illumination of Mount Hood

Now with a building, the next step was to secure the building to the mountain. In July, Dee Wright, the Chief Government Packer in the Mt. Hood district had 10 mules pack a mile of quarter-inch cable to the summit. Elijah Coleman returned to be the lookout man. After a shopping trip to the city in August, lookout Coleman said that being up on the mountain is like Godís country, and the atmosphere of the lowlands was depressing after becoming acclimated to the high altitude. Mr. Coleman said that the frequent visits from parties making the ascent of the mountain prevent him from becoming lonesome. His recreation came from testing astronomical and geodetic instruments.

In September, the efficiency of the Forest Service telephone line to the summit was demonstrated when W.D. Scott, Division Equipment Engineer of the Pacific telegraph and Telephone company, visited the mount Hood lookout station and conversed with S.H. Hess, Transmission Engineer, at San Francisco, California, a distance of 900 miles horizontally and nearly two miles vertically. The results of the test were so satisfactory that plans were made for a test telephone conversation between the lookout on Hood and the Forester in Washington, D.C. Officials of both the Forest Service and the Telephone company said that such a conversation could be successfully carried on.

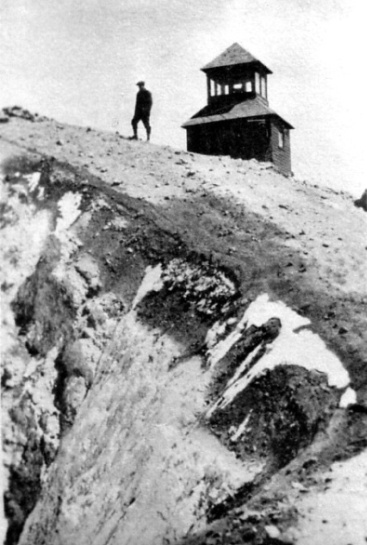

The cabin was built by Elijah Coalman. The building is of Mr. Coalmans own design and was approximately 10 x 12 feet, on the ground, and will topped by a tower that contained the equipment necessary for the location of fires. Mr. Coalman had much experience in the construction of buildings that are to be exposed to rough weather. He designed and built the Government Camp Hotel at the base of Mount Hood, on the south side. The equipment for the lookout station, including the fire finders and all the appurtenances used in a Government station, was stored that first winter in the hotel at Government Camp. It is presumed the majority of the lookout was built in late 1915 (October 1 was the planned finish date) because the cupola was up and running in 1916. Surprisingly, no news articles are found about the finishing of the cupola. His last load of gear that he carried up, was a load of nails, hinges and other hardware totaling 120 pounds.

Building The Cabin

The lookout Elijah Coalman was injured while fixing a telephone wire. He lost his footing, and fell, landing in a crevasse. When he lost his footing, he started several stones to rolling, and one fell on his chest, just over his heart. He was unconscious for about an hour, but recovered enough to get back down to Government camp. Due to this fall and some of his previous accidents, Coalman resigned from his post as lookout duty. He wrote a letter to T.H. Sherrard of the Forest Service setting forth the reasons for his quitting the service. Two years ago he fell through a crevasse above Crater Rock. Since that time he has had heart trouble. Earlier this year, he started up the snowbank near the Crescent crevasse, and was crushed by an avalanche. His heart trouble was made more acute by this latter accident. Mr. Coalman expresses his regret at leaving the forest service and characterizes his work in it as a source of lifelong pleasure.

Elijah was replaced by Mark Weygandt. At the end of September, Mark witnessed a landslide moving an enormous mass of ice and stone down the northeast side of the mountain. The slide filled the east fork of Hood River at its source and has turned glacier water into the middle fork. Old-time mountaineers say the peak in 1918 was more bare than anytime in the previous quarter of a century. With the light snowfall the previous winter, slides and avalanches were more frequent on the sides of Hood.

Year 1918

Year 1917

At the end of August, a Miss Alma C. W. of Tacoma was badly injured by a falling rock and was rescued thru the efforts of Elijah Coalman. For the second time, Coleman had made his body a human sledge and thereon conveyed the victim to safety. Coalman, detecting the accident from his lookout, telephoned to Cloud Cap Inn for a relief party and then rushed to the rescue. After he had applied first aid, he lay prone on the snow, and holding the injured woman, sled down.

Year 1921

The lookout was A.T. Mass. In mid-July, he greeted a Mazamas climbing party of 160 climbers serving hot tea and soup. The party was under the direction of Eugene H. Dowling, which started with 170 climbers. In accordance with the club policy, the party was made up of anyone wanting to scale the peak whether or not they were Mazamas. In the party more than one half were women. Leaving Portland in the afternoon, the party went to Government camp for the night and at 3 a.m. commenced the climb. The summit was reached at 10:15. During the climb a forest patrol airplane took pictures of the groups.

Year 1919

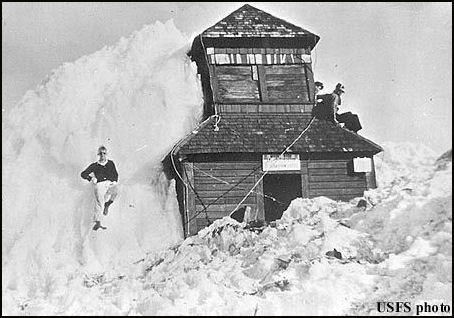

Elijah Coalman was back. He returned after his long rest after the bad fall he took the previous season. This time, however, he had an assistant, G.C. Maroney. When their season started, the station was still under snow, but Coleman and Maroney dug an entrance to the lookout house. Transporting the radio equipment up to the summit was very difficult so some wireless test phones were used. A 47-foot-tall bamboo mast was made which was made into sections, all weighing 80 pounds. One Mr. Allen designed it with the help of Coleman and Maroney assisting Mr. Allen in setting up and testing the instrument. The first fire report using it was a call down to Government Camp giving information about a fire on the Warm Springs Indian Reservation. The hope was to get the new system to be able to communicate with the District Forester's office in the Post Office Building in Portland. Also this year, lookout Marony found forty-four bones sixty feet below the summit rim. The bones belonged to an Elk or Moose. It was a mystery how such a large animal got to the summit over the glaciers and steep slopes. The bones eventually made it to the Oregon Historical Society who placed them in display at the Portland Auditorium.

Year 1920

In February, a newer wireless telephone (aka Radio) arrived at the Forest Service Headquarters. It was taken up and installed in the summer to replace the experimental one used in 1919. The radios had a range of 100 miles and were valued at $2000 apiece. The lookouts this year were A.T. Maas and W.C. Kelly of the Forest Service. They locked up the cupola at the end of October for the winter.

Year 1922

The lookouts were Charles A. Phelps of Gresham and Sam Rotsky as assistant. The lookouts started the season by placing climbing ropes on the mountain. Charles wrote a letter describing their experience during storms: Whipped by the sleet and snow and terrific wind up here out telephone line became broken. Sam Rotsky and I decided we would find the break, for Uncle Sams business can not be neglected. The thermometer showed 22 degrees below zero. We felt our way along the awful wall of the mountain, with the sleet covering us like masts of a ship at sea. It was 10:30 before we finally found the break and got it fixed. Then we literally crawled back up the mountain to the lookout cabin. We were again in connection with the world. 'I am in a tower 11,225 feet above the sea. During the electric storm, the telephone spits fire with every flash. The nail heads around the cabin walls look like flakes of fire, and the wires of the telephone like long strings of gold. I am walled in in a seven-by-seven room, with two windows making up each side. When the keen flashes come, I go stone blind for a few seconds. Clouds go by in a whoop. It is hard to imagine the force of the storm. I wish the Mazamas were up here to keep me company. I guess I will have to get the Boy Scouts to make me a member. I've nearly passed the test.

This experience above was described in more exaggerated fashion by the papers: "Late in the afternoon of August 11, a fire lookout on a 11,250 foot glacier peak climbed back to his lookout, after having been part way down the mountain for supplies. A thunderstorm having passed over the mountain late in the afternoon, upon reaching his lookout he immediately tested his phone, for he knew there would be lightning fires to report. He found the instrument dead. It was up to him to reestablish communications with the fire dispatcher. So he started out down the peak, over the 800 feet almost perpendicular face of a glacier full of crevasses, following not the rope trail but the telephone wire, to find the break. The storm was still in progress. He finally located the break at 11 p.m. on the very brink of a deep crevasse on the almost abrupt face of the glacier, and there, alone in a snowstorm and the darkness, having dug a footing with his icepick, with the aid of a pocket flashlight, he repaired the wire. He then climbed back to his lookout again and got the world outside. This was a part of his job and he did it. The peak was Mt. Hood, and the man was Lookout Charles Phelps."

In October, the lookouts put in a new floor at the lookout cabin, the old floor being worn out by calks. The lumber was sawed in 4-foot lengths at the Sandy Lumber company mill, packed on a horse to the turtleneck and from there taken up by hand. About 1000 visitors climbed to the cabin that summer. Phelps has also packed in his supply of coal oil for next season.

Year 1924

The papers reported that the tiniest campfire can be spotted from the lookout cabin, and many a camper who thought he was far away from any ranger has been surprised to have a forester stop by and inform him that Uncle Sam knows he is there and to be careful with his camp fire.

On July 20, after a night of mist, rain and sleet, Lookout Charles Phelps climbed down the mountain from his cabin until he came to the break in the telephone line on the triangular moraine, where a large rolling rock had cut the wire in two. Repairing the break, he climbed back to the top, called up the dispatcher, ate his breakfast and was ready to begin his day's work as lookout man. On this day, there were 268 visitors reaching the top of rugged Mount Hood.

In September, Lookout Charles Phelps was injured by a falling boulder while attempting to escape the force of the electric storm around the peak. His ankle was sprained and his foot bruised when the rock struck him as he was going down the mountain. He camped for the night in the bottom of the crater and made his way to Government camp the next day.

Year 1925

This year the lookout was Fred Schmeling, of Cascade Locks. He took the place vacated by John Calverley, Sr., who found after a few days on the job that he was unable to stand the altitude and was compelled to come down to a lower level. Mr. Calverley and Sam Rotschy worked the telephone line from timberline to the summit and did most of the packing of supplies from the cache below Crater Rock to the top. Fred Schmeling finished this packing and made his residence on top. In September, the lookout cabin was struck by lightning three times during a severe electrical storm. Fred escaped without injury, but he had to patch holes in the cabin made by the lightning. Two small fires were started by bolts, one at Potato Butte and one at Tom, Dick and Harry Mountain. Around mid-September, the lookout was closed early to prepare for some expected bad incoming weather. The lookout Fred Schmelling took the ropes down.

Year 1932

The lookout was Mack Hall this year, a University of Oregon student who was well liked. Jokingly he told climbers he would gladly pay 35 cents a dozen for eggs delivered, although the market price was 20 cents. Barney Young, a bank clerk, climbed Mount Hood early one morning and presented Hall with a dozen eggs, collected the 35 cents, and descended again that night. Days later, the lookout was awoken again by other egg-delivering enthusiasts. NO MORE EGGS, he ordered as thirteen dozen had been brought to him by as many persons. In mid-September, Mack took down the ropes, rolled up the telephone line, closed the lookout cabin and ended the official climbing season for Mt. Hood.

Year 1927

In this year panorama photos taken by R.T.C.

Year 1926

The season started a bit early for the summit station, around June 25. In late August, Sam Roctschy, Edward Schenk and Dean Van Zant were descending from the lookout station in a terrific storm of wind, snow and sleet. They had great difficulty keeping their footing and the force of the wind was so great as to hamper breathing at times, they reported. They had been packing supplies and parts for a lightning arrester to the lookout. They also strung a new phone line to the top. Dean Van Zant was a new lookout this year but had been a guide and hotel man for the previous five years at Government Camp.

Year 1929

The lookout person was again Robert G. McVicar. Starting in July, the mountain officially opened to climbers as ropes were put up, telephone connections had been replaced by the forest service and lookout R.G. McVicar, was at the top of Hood for the season. A few weeks later, Robert looked out his lookout cabin window and saw nine persons climbing the peak. Upon arrival, McVicker's wife was in the party. She spent the summer with him, and acted as hostess to mountain climbers.

Year 1928

The lookout person was Robert G. McVicar. He started his work at the beginning of July. The following week, a wedding party arrived including his bride. Robert was married to Miss Elva Taylor, former school teacher of New York City. That summer, his wife stayed with him on the mountain for several weeks. They were united in marriage by the Rev. T.H. Stains of Selah, Washington. It was the second wedding to be performed by Mr. Stains on the summit of Oregon's highest peak. By mid-September, Robert was winding up telephone wires and fixing things up for winter. The ropes were taken down just before a large storm hit with deep snow on the mountain. It was estimated that 2000 people climbed Mount Hood during the season of 1928, of whom 1109 actually registered with the lookout Robert McVicar the lookout.

Year 1930

The lookout person was again Robert G. McVicar, and again he tried to get the lookout open and ropes set up for mountain climbers by the July 4 holiday. Mrs. McVickers, who spent the past two summers with her husband on the summit, again joined him there after a few weeks. Robert closed down the lookout and removed the ropes in mid-September.

Year 1931

Lookout Robert McVicar and his wife were on the mountain again. They were anything but lonesome with an average of over 250 people per week in July making the climb to the summit.

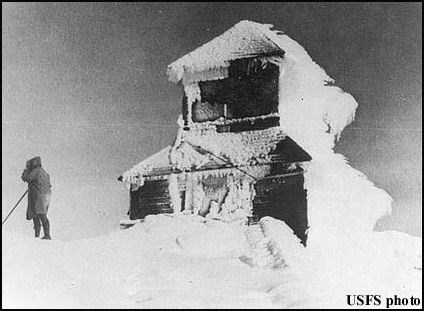

Year 1933

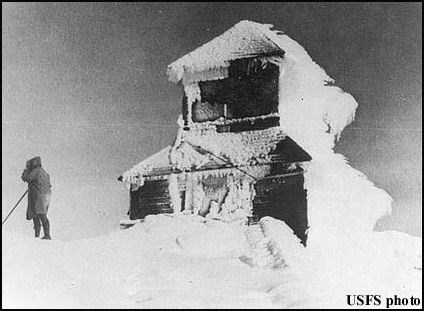

In March, before the season started, the previous years lookout, Mack Hall was killed when his car skidded in loose gravel, plunged over an embankment east of Eugene and crashed to the railroad tracks below. Also in March, the first mountain climbers of the season realized the sturdy built lookout cabin had been practically destroyed over the winter. Although fastened down by cables anchored to rocks, the cupola had been nearly torn off and the building had been pushed partly on its side, cracked open, and broken away from two of the cables. The inside was filled with snow and ice. It was a foot off its foundation and leaning to an angle of 60 degrees. These first climbers who reported the news were Ray Lewis of the Mazamas, Everett Darr of the Wy-east Club, and Miss Eisa Hanff of Spokane. Later in July when the fire season started, it was Ray Lewis who took the job on top. When Ray requested a bottle of beer and some rat poison to oust rodents, the person that came to his rescue was his earlier climbing companion Everett Darr. Apparently the high climbing rats had made their way to the summit and were devouring the supplies of Ray Lewis.

Year 1934 and Beyond

No lookout, the structure was abandoned. An article in the Sunday Oregonian reported at the end of July 1936 that the summit lookout on Hood had not been used for the past few years because layers of clouds often hugged the mountain between the summit and timberline, completely hiding the valleys. This condition existed even on otherwise clear days and so the Lone Fir lookout above timberline and at an elevation of 7000 feet was used instead. In reality, it seems the damaged cabin was abandoned after the 1933 season. The cabin slipped off the summit in 1941. In 1970, the first lookout person and builder of the lookout, Elijah Coalman, at age 88, died in a La Habra, California rest home. He first climbed Mt. Hood in 1897 and then climbed it 586 more times before he retired as a guide in 1928. The first party he ever guided to the summit was in 1905.

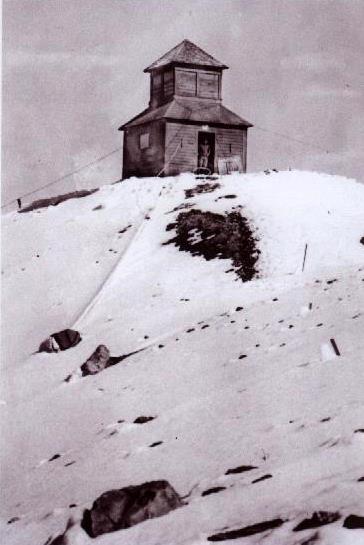

1928

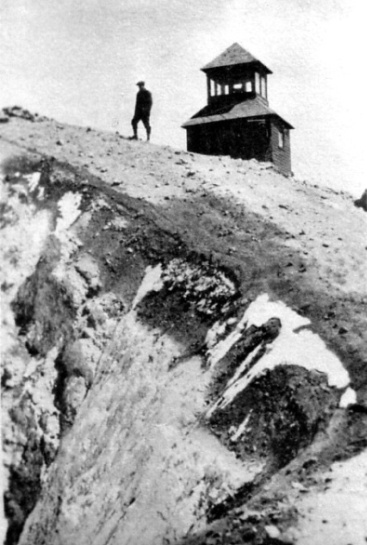

1921

1934

Just a firefinder in 1915

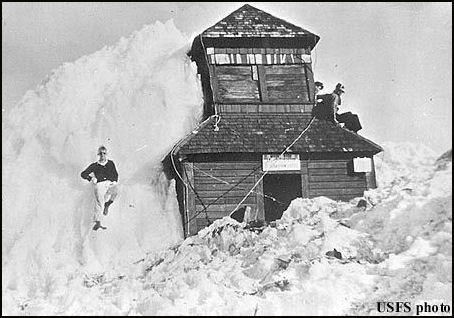

1918

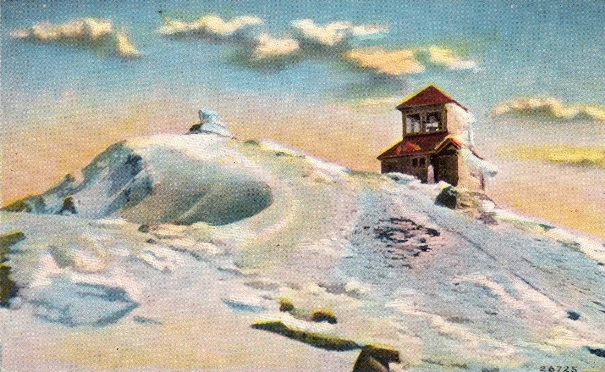

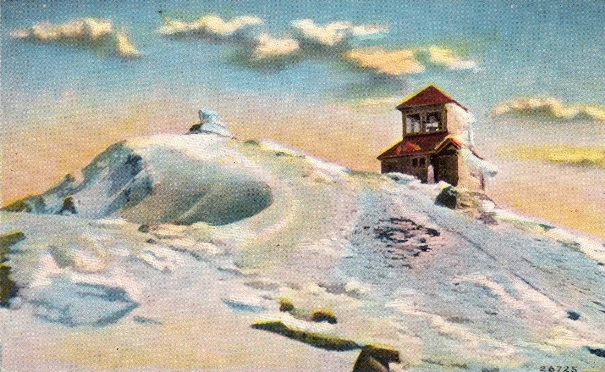

Postcards of Mt. Hood

July 2015, photo by Will Lehmann