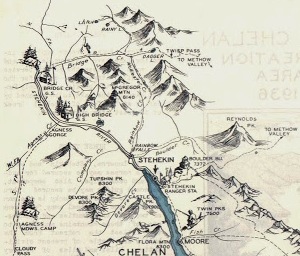

Dominating the up valley view from the top of Lake Chelan at Stekehan, McGregor Mountain rises up from the valley floor over 6,000 feet. With an elevation over 8,000 feet and 2,122 feet of prominence, it stands high and isolated from the others. McGregor has a fascinating history with fire lookouts and use as an AWS site during WWII. Reaching the summit requires one of the largest trail elevation gains followed by a dangerous scramble up narrow ledges among cliffs. The lookout house was likely the most difficult to reach in Washington, lasting from 1926 to 1955. The National Park website says: reaching the summit requires route-finding and exposed scrambling over talus and rock, and should only be attempted by those with the skills and experience to undertake this climb.

History

1916:The mountain first used a camp at timberline.

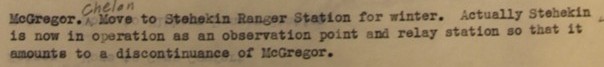

1926: A cupola cabin was built on the summit by Bill Lester and Paul Heaton. During that year in November, "During out last lightning storm, the lookout house, while still under construction, was hit by a bolt on the corner of the tower. From there the charge ran down the 4x4 supporting the tower, splitting it into splinters and cutting off above the guy wire. The metal shingles along one corner were thrown in all directions. In running down the guy wire, it exploded a 600 pound boulder to which the cable was anchored, then jumped to the drag line on the 1,400-foot double tramway cutting the drag line at each place it ran through a block. This allowed one carriage to run to the bottom of the tram which demolished it and let down one standing line, one eighth mile of telephone line was heated to a high temperature and left a kink in it about every six inches. Mr. Ramm, the carpenter, and Mr. Heaton, the lookout, were at their camp one-half mile below the lookout house when the bolt struck. The telephone was unhooked and the boys were getting supper when Mr. Ramm was knocked unconscious for about twenty minutes, receiving a burn as large as a dollar on the top of his head and many small burns on the bottom of his feet. Mr. Heaton was not injured, due to the fact he had rubber shoes on, having no nails in the soles. Mr. Heaton and Mr. Ramm were at least ten feet from the telephone line. Mr. James, the cook at the road camp, eight miles away, was talking on the phone at the time the bolt was released. He was knocked unconscious for a couple minutes, receiving burns on the cheek, arm and feet. Mr. James, otherwise known as Dunc, was about to report rain in that locality when hit. It was rumored that Dunc is in the market for a good lightning arrester that can be carried in the hip pocket or elsewhere on his person. Roy Weeman" (Six Twenty-Six)

July 1929: "Yes, we still remember that lightning struck the McGregor Lookout house while it was under construction. The elevation of the peak is 8,160 feet, and the house was located on the top. We have also in mind several trees on the top of the ridges that have been struck by lightning and set fires on his forest. R.L. Weeman" (Six Twenty-Six)

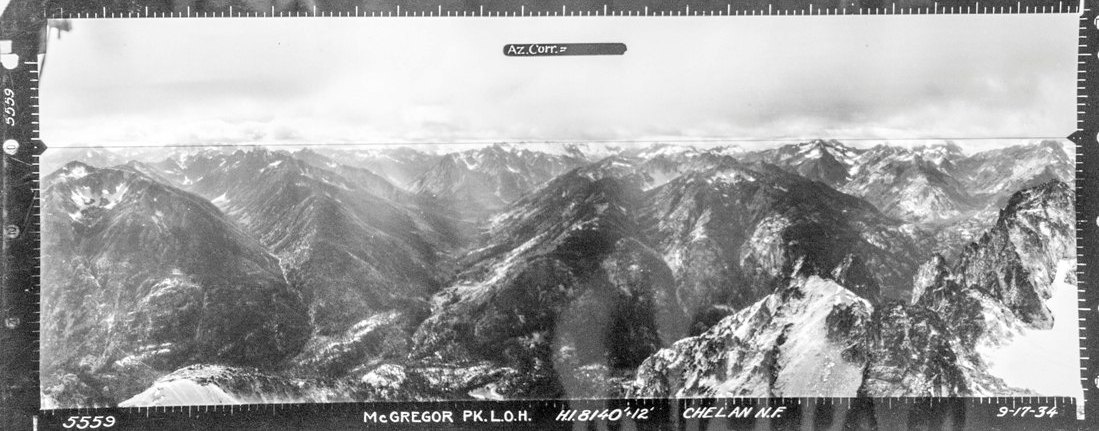

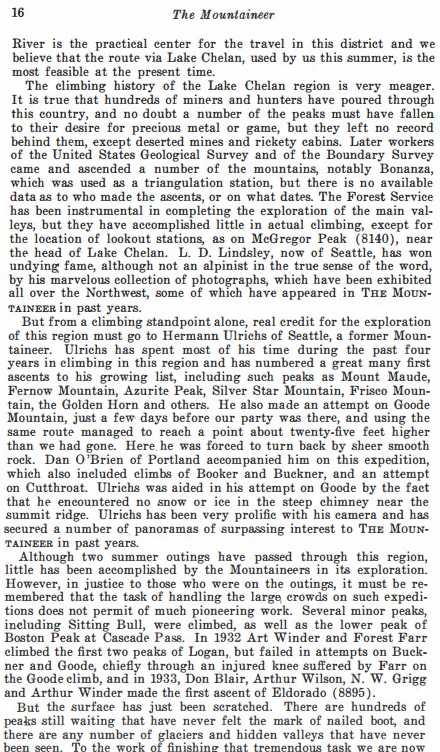

1934 Mountaineers Annual: The climbing history of the Lake Chelan region is very meager. It is true that hundreds of miners and hunters have poured through this country, and no doubt a number of the peaks must have fallen to their desire for precious metal or game, but they left no record behind them, except deserted mines and rickety cabins. Later workers of the USGS and of the Boundary Survey came and ascended a number of the mountains, notably Bonanza, which was used as a triangulation station, but there is no available data as to who made the ascents, or on what dates. The Forest Service has been instrumental in completing the exploration of the main valleys, but they have accomplished little in actual climbing, except for the location of lookout stations, as on McGregor Peak (8140), near the head of Lake Chelan.

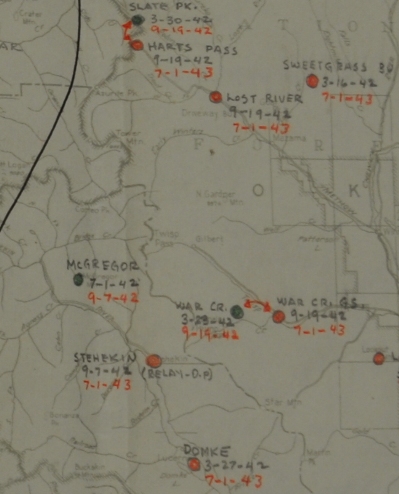

1942 Aircraft Warning Service History: Served as an Aircraft Warning Station from July 1, 1942 to Sept. 7, 1942.

July 25, 1942 To: James Frankland from Francis T. Carroll, AWS Inspector

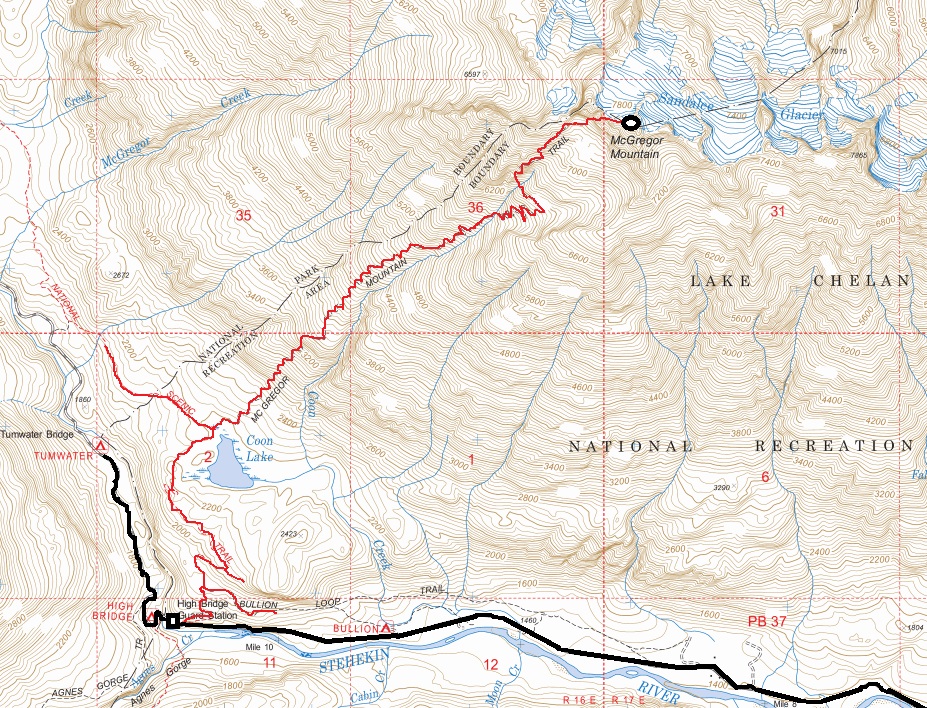

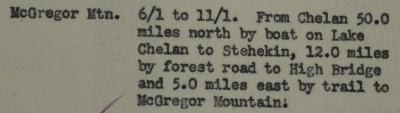

I made the trip to the McGregor O.P. and lookout with P.A. John Oladney on July 16. This post is 48 miles by boat from Chelan to Stehekin, thence 11 miles by road to the High Bridge Guard Station. It is 8 miles by steep, low-class horse trail to the end of horse travel. The remaining ½ to ¾ mile must be made on foot over talus and rock ledges and bluffs. The route is marked with painted yellow arrows. It is precipitous and in several places very narrow. When there is snow or ice, it is not safe to travel. Ice formed after the storm on the afternoon of July 16, making it impossible for the men to go down over the rocks on the morning of July 17 to repair a break in the telephone line. The peak is 8,140 feet high and is blanketed by clouds during stormy weather. This means that the point can only be occupied during the summer. The peak is quite windy and the resulting noise reduces the possibility of hearing planes. All supplies must be back-packed from the end of the horse trail. Materials for the R-6 with cupola lookout house were transported for the last ½ to ¾ mile by aerial tram which had to be abandoned because winter storms wrecked it annually. The building is situated on a rock promontory which had to be flattened and only sufficient space for it was provided. The observers cannot walk around the building. An open toilet which should be replaced with one of the R.6 Plate II-A type. Garbage and cans are dropped over a very high bluff into an inaccessible canyon area. Ranger Shambaugh wants to board up the inside to the bottom of the windows where the rain and melting snow now seep in. He also wants to put up opaque roller shades on the windows on the first floor so a light can be used. I concur in these recommendations if it is decided to continue to use this peak as a summer post. He also wants to improve the trail. I question the expenditure of AWS funds for this purpose because of the doubtful value of the peak for AWS purposes. A grounded telephone line parallels the horse trail the entire distance. From there, emergency wire is used to the top. Snowslides, while not an annual occurrence, have taken out both the trail and telephone line in the past. The emergency line broke between 7:00 A.M. and 9:00 A.M on July 17. Test calls at 4-hour intervals with Stehekin R.S. which is the relay station. Radio communication contacts hourly from 5:50 A.M. to 5:50 P.M. with Domke to insure communication. Donald Frank is the Chief Observer and is paid from regular funds as a lookout. He is a high school graduate. David Van Lieu is the other observer. He has finished one year of Law at Washington State. Both boys are intelligent and have studied the instructions. Only one flight has been observed and reported. Not all essential information was entered. This was pointed out and they entry completed. The record of radio and telephone checks was being kept in a separate notebook. I suggested they be entered in the log and that entries showing delays in reporting telephone trouble, weather conditions, visitors, etc., be shown. Thee matters were discussed with Ranger Shambaugh who made notes to provide for taking up with the observers. Test flash messages are being tried to give both observers and relay operators experiences in submitting and recording. Neither of there men goes to fires. The observers were working on an 8-hour schedule arranged by them selves. This gives them 8 hours rest every other night and both stated it is satisfactory. This was discussed with Ranger Shambaugh and he will keep a check on how it works out and make a change if necessary. The Ranger told me before I went to the peak that some difficulty developed about a week previously but he had settled it to the apparent satisfaction of both men. Each of the observers is required to make one trip each day, when the roads are free of ice, to the end of the horse trail to back-pack in supplies and fuel, either gasoline or kerosene. Gasoline was being used for fuel. Both men stated that fumes result. A new combination 2-burner cooking and heating kerosene stove is at the Stehekin R.S. and will be taken to the lookout soon. It is a Coronado A 211 GA guaranteed to be odorless and can be secured from the Gamble Stores. Wood is out of the question for fuel. A folding canvas cot is provided. It was broken and its condition reported to the Ranger who stated it would be replaced the next time the pack train goes in. Snow from the Standalee Glacier which extends to within a few feet of the lookout is the source of water. I saw no place along the trail which I considered suitable for a winter post. The noise of the river at the High Bridge G.S. eliminates this place from consideration. A list of other possible winter sites in the order of their desirability was given by Ranger Shambaugh and P.A. Gladney. These possible sites are:

Bullion Flat, about 1 miles below High Bridge, Sec. 2, T. 33 N., R. 17 E., along road and phone line, no buildings. Bridge Creek at old guard camp, Sec. 21, T. 34 N., R. 16 E. On road and phone line. No buildings. Stehekin R.S. Adequate facilities. Sec. 6 T. 32 N. R. 18 E. now used as relay station.

Recommended Action: (1) If a yearlong O.P. is needed in the area, the Stehekin R.S. appears to be the most logical point. If a point further West is desired, install the necessary improvements at Bullion Flat.

(2) If only a summer station is needed, the building should be sealed below the windows and shades provided.

Forest Lookout, By Ella E. Clark (National Geographic Magazine, July 1946)

(Ella

was a college teacher who had decided she wanted to be a lookout and write about it. She spent two summers as a lookout in the

southern Washington Cascades, but on McGregor she held out for less than two weeks. Below is some of what she wrote for National

Geographic during the two weeks.)

My present lookout in the Chelan National Forest consists of a single window-enclosed room measuring 111/2 by 11 1/2 feet. A ladder starting from about the middle of the room leads to the tower and the firefinder. The room is furnished with bunk, a table, a built-in cupboard topped with a work table, and a stove. Here, far above the tree line, I burn kerosene. Cooking equipment is good and when kept up to the standard Forest Service list, is complete. The white china dishes are substantial – twice the thickness and weight of my breakfast pottery at home. Floors are bare; windows of course, must remain curtainless. In these one-room stations there is no wall space, not even for hanging ones clothes. My other 2 lookouts had a good little cellar in the side of a hill with shelves and a ventilating system, keeping butter firm and vegetables fresh surprisingly long. This location my “Frigidaire” on warm days, is a metal container forced into the snow between two rocks. Previously I have disposed of my garbage by burning what I could and then putting the rest in a pit dug for the purpose and fitted with a lid. Here, where I can neither burn nor bury, garbage disposal is more primitive. When I have emptied a can, I step to the door and toss it three or four feet. For a few seconds it knocks against the rocks which I cannot see, and then it reappears, a moving speck on the snowfield below. It still goes against the grain to dispose of refuse in that way, even though I am sure that no human being will ever see that tin can again and even though I can think of no better method of disposal.

Probably all of us weary of the wind. Many times I have been awakened by it and have been grateful for the eight heavy cables which keep the cabin in its place at the edge of the mountain. Young boys, I was told last summer, have telephoned during a heavy wind in the middle of the night, just to hear the reassuring voice of the motherly woman at the switchboard below. This summer my water supply, a glacier, is but a few yards from the door. I melt the snow, strain the water through a cloth, and boil what I drink. [Speaking of hardships] Rivaling these discomforts this summer, and perhaps surpassing them as I look ahead, is the lack of opportunity here for healthful outdoor living, a necessity of my summers. Here in the center of far-reaching space, ten miles from anyone, there is not enough space inside the cabin, nor substantial footing outside, for even vigorous setting-up exercises.

For the fourth successive day I am enveloped in fog so thick that I can see but a few feet from the cabin. Though it is the middle of July, there are frosts and ice outside; there have been sleet, howling winds, and flurries of snow. My battery radio, brought up for news and pleasure, is silent in the cold. For more than 48 hours my telephone has been dead, my only contact with the outside world being hourly radio communication with a high school boy on a lookout 20 miles away. Alpine climbers among my readers may prefer my present view of the Cascades in northern Washington, especially if they do not contemplate spending two months upon this pin point of rock, with yawning abysses on three sides and a steep descent of boulders and loose rock on the other.

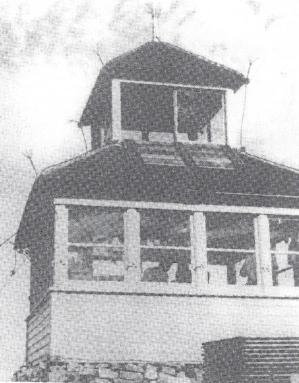

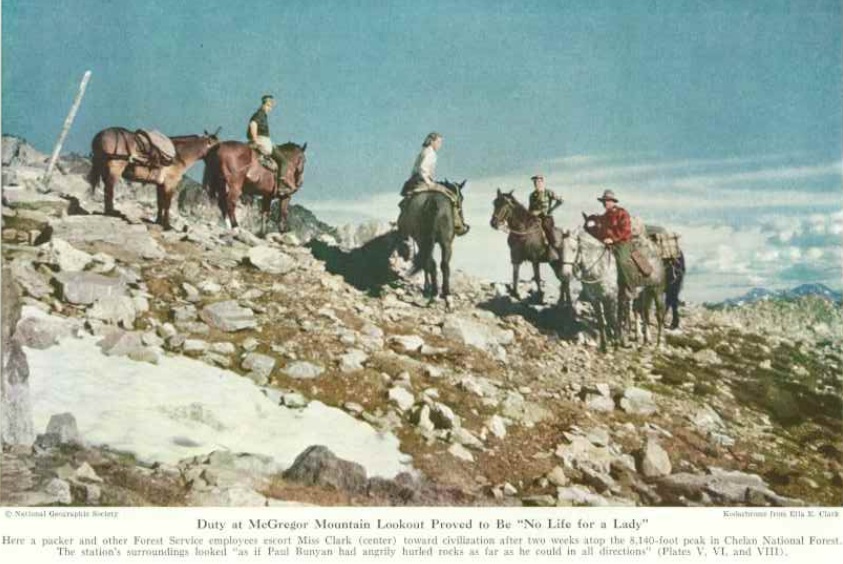

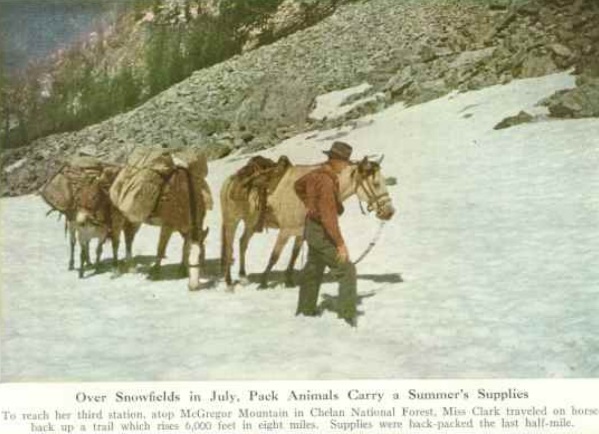

Climbing to McGregor Lookout: To reach my third lookout station, one must come by boat to the head of Lake Chelan, travel for eleven miles on a rocky Forest Service road along the Stehekin River, and then climb eight miles of trail, rising 6,000 feet. The trail leads first through forest lush with thimbleberry and with bracken often horse-high, then through a wild chaos of rocks, tumbling streams, alpine firs and alpine larches, small meadows bright with heather, paintbrush, and blue lupine. The trail has 187 switchbacks, I am told, and I am willing to accept the number. At times each new switchback brought a wider vista; al little more of that snow-capped ridge became visible; the whole crest of another mountain appeared behind a crescent-shaped valley head. A few times on the fifth of July we dismounted and led our horses across snowfields. After three hours we were above tree line, even above the dwarf conifers. About one-half mile from McGregor Lookout, perched above us on a perpendicular wall of rock, the packer left me and my summers supplies and took the horses back to High Bridge, from where next morning he would return with the kerosene for the summers cooking and heating.

In the shelter of a boulder, shelter from both glaring sun and chill wind, I watched for nearly two hours while the trail crew brought a telephone wire down from the lookout. That is, I watched as often as I could endure the fascinating horror of seeing a Forest Service official and three youths bring or throw a copper wire from crag to crag, seeing them climb over sharp ridges and along ravines where a false step would be the last step. Yet a husky high school boy whistled as he worked and laughed as he slid down the snowfield. In his hand he held a rock attached to the wire, the rock which he had flung from the last sharp ridge above the snowfield. Never again will I look casually at telephone lines in hazardous places.

A half-mile is a short distance except when it is turned on end. This last half-mile to the lookout required one hour of climbing and of stopping for breath in the rarefied air. Up we went across the snowfields and over the rocks, the leader and the boys carrying 40 to 60 pounds apiece in their backpacks and I feeling that my camera equipment and ski jacket were sufficient pack for me. I literally followed in the footsteps of the leader, and all of us kept our hands free to balance ourselves on the rocks wherever the trail was especially steep and narrow beside an abrupt drop.

From book: Firewatchers of the

Cascades and Olympics

When Ellis Ogilvie was working for the Forest Service in the early 1940’s, he overheard bits of radio conversation between McGregor Mountain and the Stehekin Ranger Station. The lookout talked about mountain goats, glaciers, and glimpses of the headwaters of Lake Chelan. It sounded like a great place. The next season, 1944, Ellis applied for the position. His supervisor stared at him silently before observing, “Well, I once asked for that job. That makes you the second one ever to volunteer for McGregor.” Packing in took two days. At 7,000 feet Ellis and the packer reached a small meadow, beyond which the peak rose precipitously for another 1,000 feet. “This is as far as I go,” the packer announced. Pointing at a 700-foot cliff, he added, “There’s the trail.” He began unloading Ellis’s supplies, which included 100 gallons of stove oil to keep him from freezing up there. Ellis stared at the cliff. “What trail?” he asked. “See those red paint splashes? They mark the best ledges to climb on.”

According to Bill Lester of Winthrop, who helped put the cabin with cupola on the peak, it was done with cables to tram up the materials. During lightning storms, Ellis recalls, “the network of copper cables around the cabin carried so much St. Elmo’s fire, it looked like the Standard Oil station lit up with blue neon tubes.”

Fire

Lookouts of the Northwest

The summer opening of the station meant several hard days work for four men. Long sections of phone line had to be replaced several times after lightning dissolved it. Winter avalanches left the wire a twisted mess a mile down the gully every year. The telephone party line linked guard stations at High Bridge, Bridge Creek and Stehekin with his two peers atop Goode Ridge and Stiletto Ridge. The last lookout on McGregor was Jack Elliott. Jack and the other lookouts that served on McGregor would watch at noon as the daily mail boat would dock far down in Stehekin with its load of tourists. An hour later, the ship left again with virtually all of them, cutting a wide furrow down the middle of the mile-wide fiord to disappear around the first bend 25 miles away. Thus was McGregor’s touch with the outer world then, as it is today.

1949: McGregor was de-commissioned without ceremony.

1955: Burned down by the Forest Service.